Fractals!

My history with fractals. How I stumbled across them as a kid, wrote some fractal generators, and discovered some interesting fractal formulas.

How I met fractals

I got introduced to fractals when I was maybe 14 years old. I grew up in Croatia in the '80s, then still part of Yugoslavia, and there were 3 monthly magazines you could subscribe to in Yugoslavia if you were a computer afficionado: “Moj Mikro”, published in Slovenia, and “Računari” and “Svet Kompjutera”, both published in Serbia. Naturally, I was subscribed to all three.

I don’t remember anymore which one of these three had an article around 1987-88 about the Mandelbrot Set, illustrated with black-and-white pictures of some interesting zoomed-in areas. I was immediately mesmerized by the beauty of it all. Despite not having any prior knowledge of complex numbers, I managed to write a small program in Commodore 64 BASIC (yep) to compute an image of the Mandelbrot Set in C64’s 160x200 resolution with 4 colors.

As you can imagine, it was slow[1]. Like, go for lunch and come back to see it rendered few more columns of pixels slow. It wasn’t until several hours into runtime that I could tell if it even computes the right thing! Luckily, it did.

Writing my first proper fractal generator

Maybe a year later, I managed to convince my parents to sell the Commodore and instead buy an Atari ST. Going from a 1MHz 8-bit CPU to a 8MHz 16-bit CPU was a huge leap. Naturally, I wrote a fractal generator for it. By then, Fractint was around on PCs, and I learned a lot from it, e.g. some tricks to speed up computation. Most importantly, I learned that you can generate fractals from pretty much any formula. The generator I wrote ended up supporting a whopping 39 formulas! It supported not just the Mandelbrot/Julia set pairs, but it could even plot attractors.

Finding a new fractal

Many of these were well-known formulas, but of course, I wanted to know if I can find some hitherto undiscovered formulas, so I started experimenting with them. I didn’t have any methodology to my exploration; I was just assembling formulas by randomly constructing algebraic expressions and then watching what fractal image they produce. Most of the time, the generated fractal would be quite boring, often just a black circle surrounded by a sea of blue. It was summer, I was 16, so I had other things to do too (swimming, playing table tennis, reading books, being hopelessly clumsy around girls), but from time to time especially when it was too hot outside I’d stay in my room, sit in front of the Atari, and think of more ways to contort algebra.

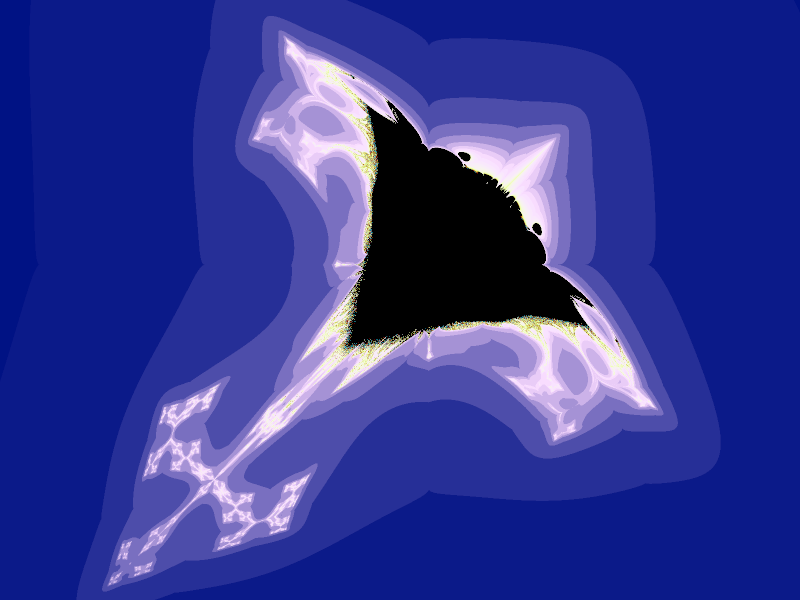

Eventually, one formula caused this to appear on the screen:

Wow! I could not believe my eyes, but it was real.

(As a sidenote, this is an actual rendering from my original fractal generator software I wrote for Atari ST back then. I recently managed to finally have it transferred from its original floppy disks where it spent a good 30 years without getting corrupted, so I can now run it in an emulator!) I put the source code up as a historic archive on GitHub and if you want to run it yourself, here’s an Atari ST disk image too.

In the video below, you can also see how it looked like while the software was running to render the fractal. It’s actually four times faster than it were on my original machine back in the day, as I could tell the emulator (the excellent Hatari) to run the emulated machine at 32MHz clock speed instead of its original 8MHz.

What’s the formula?

If you want a good introduction to Mandelbrot/Julia style fractals, I can recommend both an excellent 3Blue1Brown video and a similarly excellent Numberphile video. I’ll try to give you a quick summary here too, but if you’re intimidated by the math, just skip this section and keep looking at the pictures!

All Mandelbrot-Set style fractals are generated by iterating some function over the set of complex numbers. For every possible constant value $c \in \mathbb{C}$ we compute the sequence of $z_0 = 0; z_n = f(z_{n-1}) + c$ and if the sequence doesn’t escape towards infinity, then $c$ is part of the set (customarily colored black or white), and if it escapes towards infinity, then $c$ isn’t part of the set (and we color it according to some notion of how fast does it escape.)

For Mandelbrot Set proper, the iterated function is simply the square of a number, $f : \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}, f(z) = z^2$. Or, written in the $z=(a+b\mathrm{i})$ notation that decomposes the complex number into a sum of its real and imaginary parts: $f(a+b\mathrm{i}) = a^2 - b^2 + 2ab\mathrm{i}$.

The iterated function for Szegedi Butterfly 1 fractal is also easiest to express in this decomposed notation. This is the function:

$$ f : \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}, \quad f(a + b \mathrm{i}) = b^2 - \sqrt{|a|} + \left(a^2 - \sqrt{|b|}\right)\mathrm{i} $$

Finding more fractals

Now that I had this function, a trivial next function to try was to take the previous one and just swap the real and imaginary components in the function to obtain Szegedi Butterfly 2:

$$ f : \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}, \quad f(a + b \mathrm{i}) = a^2 - \sqrt{|b|} + \left(b^2 - \sqrt{|a|}\right)\mathrm{i} $$

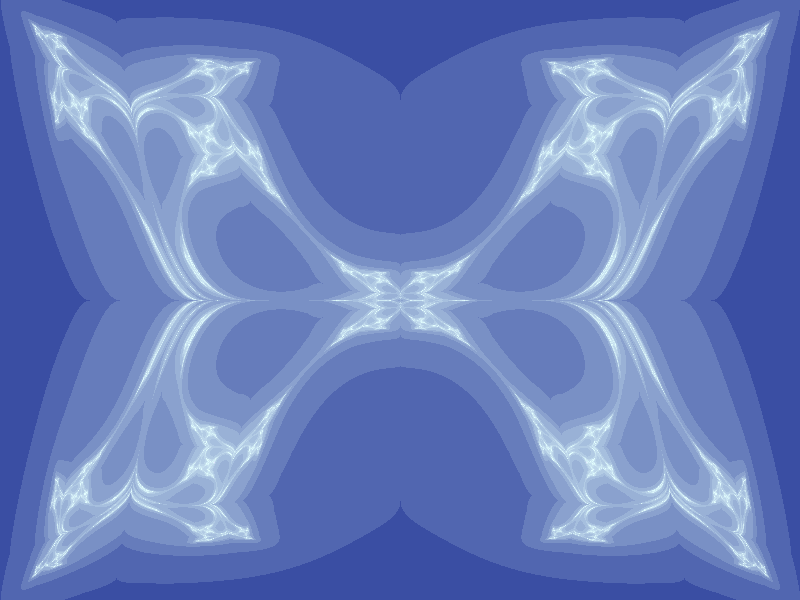

This resulted in this image:

Szegedi Butterfly fractals in modern software

If you want to explore these fractals today, I can recommend Ultra Fractal. It is commercial software but at $29 for its Express Edition it’s quite a steal (I’m not affiliated.) A nice thing about Ultra Fractal is that it has a large formula database, and many years ago I had my Butterfly Fractals added to it, so you can generate them as soon as you downloaded the formula database.

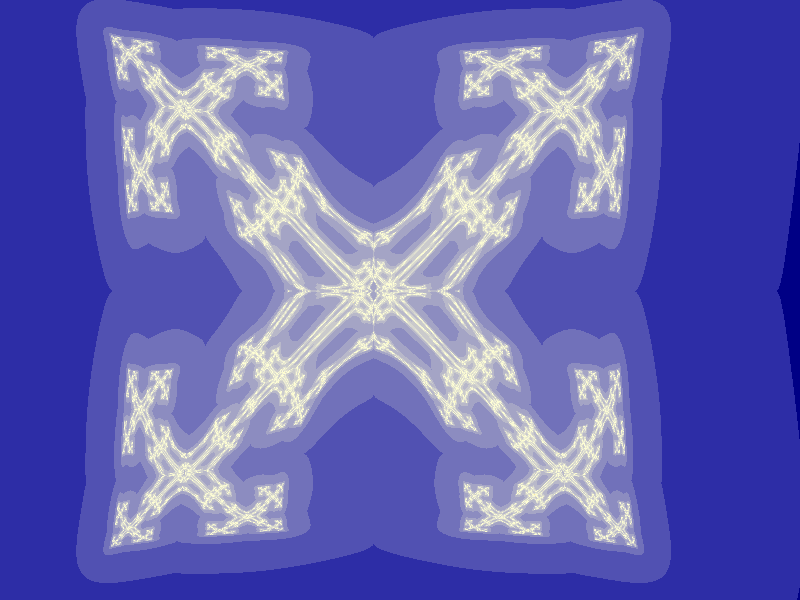

Here’s how they are rendered in Ultra Fractal, with more colors and a higher resolution (note how the horizontal axis is mirrored compared to my generator.)

In addition to the two fractals generated with the Mandelbrot-style iteration, there’s also an infinite set of their Julia/Fatou Set equivalents. Here’s a random representative of a Julia dual of Szegedi Butterfly 1:

And here’s one random representative Julia dual of Szegedi Butterfly 2:

Bioforms

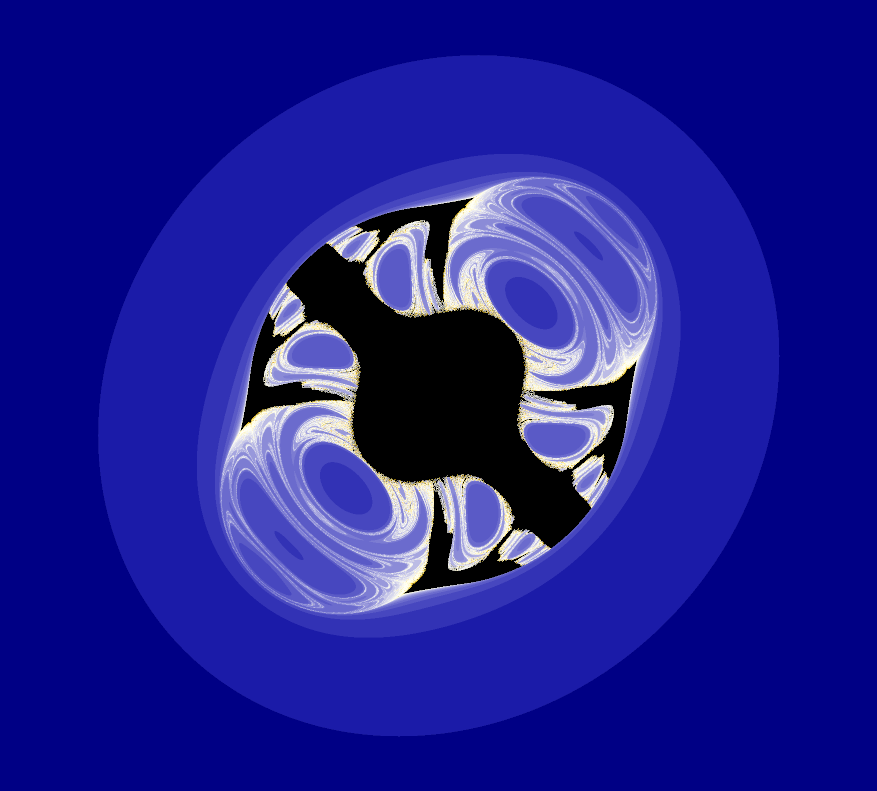

In addition to the butterflies, I also discovered another function that produces – especially in its Julia sets – something that looks very much like living cells, or maybe a cross-cut of a living tissue. I call this one Bioform:

$$ f : \mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}, \quad f(a + b\mathrm{i}) = (2 - a^2 - b^2) * (b + a\mathrm{i}) $$

Its Mandelbrot Set equivalent looks like this:

It’s however the Julia sets that really show why I named this one Bioform. Just look at this animation going through a bit of the parameter space:

So… that’s it, that’s the fractals. Again, if you want to play with them, I recommend Ultra Fractal – happy exploring, and if you find some interesting regions in them, do let me know!

Commodore 64 even had this weirdness where VIC (the video controller chip) and the CPU shared the memory bus, so if VIC was on, the CPU could use only half the cycles on the memory bus. By turning the VIC off, you could gain some speed, but it also meant that you had to blindly type the correct BASIC

POKEcommand to flip a bit in the register controlling it in order to get video output back. Exciting times! ↩︎